Condo Resources

For Owners and Strata Corporations

Smoking issues are one of the top complaints in condo complexes in BC. This is despite the fact that the majority of British Columbians do not smoke. If your Council and Strata Manager are spending valuable time addressing second-hand smoke complaints, owners can do something about it. Implementing a non-smoking bylaw is legal, protects the health and safety of all residents, lowers maintenance costs and reduces the risk of deadly and costly fires. This section is designed to provide you with easy steps to implement, amend and enforce non-smoking bylaws. It also provides different strategies for addressing complaints of second-hand smoke, whether or not you have a specific bylaw in place to restrict or ban smoking in the strata complex.

Steps to Implement

How To Go Smoke-Free: 4 Easy Steps

pdf download - STRATA CORPORATIONS - Implementing a Non-Smoking Bylaw for Existing Buildings - for printing

pdf download - STRATA CORPORATIONS - Sample Non-Smoking Bylaw - for printing

New Condo Developments

The vast majority of British Columbians don't smoke, which makes going smoke-free for new developments a good business decision. If you have a strata project underway, you can designate strata lots, limited common property and common property 100% smoke-free from the outset.

A developer won’t have any trouble attracting buyers due to high demand for smoke-free housing in BC, and the strata corporation will avoid the conflicts, costs, and fire risks of maintaining buildings where smoking is allowed.

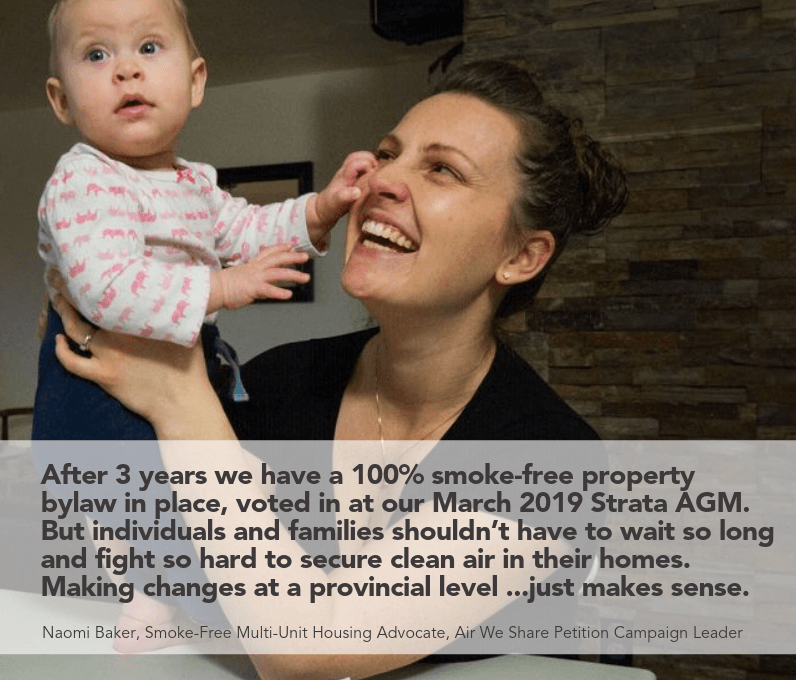

The developers of Magnolia Gardens, a new condo development in Prince George went 100% smoke-free from the get go. They wanted to promote better health for everyone, but according to Kim Croft, "the fringe benefits of higher resale prices and lower maintenance fees are a definite added bonus.”

How To Go Smoke-Free: 3 Easy Steps

pdf download - STRATA CORPORATIONS - Implementing a Non-Smoking Bylaw for NEW Condo Developments - for printing

pdf download - STRATA CORPORATIONS - Sample Non-Smoking Bylaw - for printing

Strata Councils have a duty to act on second-hand smoke complaints.

Past decisions from Tribunals and courts in BC and across Canada provide some useful guidance for Strata Councils faced with second-hand smoke complaints as follows:

- It is not necessary to have a specific non-smoking bylaw to address complaints of second-hand smoke. Second-hand smoke may contravene the Strata’s existing nuisance bylaws and should be enforced. This is the case even if the alleged violation of the bylaw affects only one owner.

Residents are protected by the common law of nuisance. The Schedule of Standard Bylaws in the Strata Property Act (SPA), Section 3(1)(a) and (c) states that an owner, tenant, occupant or visitor must not behave in ways that creates a nuisance or hazard to another person or unreasonably interferes with the use and enjoyment of their home. If residents are unreasonably bothered by smoke exposure, the Strata has a duty to enforce the nuisance bylaws and many have been found liable for not enforcing its nuisance bylaws.

Further, many Councils have also failed to take the lead on nuisance complaints when dealing with second-hand smoke. They often put the onus on complainants to prove the source of the smoke and whether in fact the smoke constitutes a nuisance. Some Stratas refuse to take appropriate action when there is contradictory evidence between residents and leave it up to the owners to resolve. Yet Stratas should recognize that they will be liable if the Tribunal finds they have failed to adequately resolve the issue.

- If a Strata Corporation has a specific ‘non-smoking bylaw’, it is the duty of Council to consistently and promptly address complaints and enforce violations of the bylaw. If the non-smoking bylaw ‘grandfathers’ existing owners, it does not exempt the Strata from enforcing the existing nuisance bylaw in response to second-hand smoke complaints.

Adopting a smoke-free bylaw provides clear rules regarding smoking and avoids having to determine whether second-hand tobacco or cannabis smoke constitutes a “nuisance” or an unreasonable interference. That said, Stratas must promptly and consistently enforce their smoke-free bylaws and have been ordered to pay damages for failure to enforce them (Cheslock v. The Owners,2021 BCCRT).

Further, Stratas with smoke-free bylaws that grandfather existing smokers still have a duty to enforce the existing ‘nuisance’ bylaws when they receive complaints about second-hand smoke infiltration coming from ‘grandfathered’ units. Investigating smoking complaints, including tribunal preparation and processes, is both time consuming, costly and not covered by most insurance plans. Given these challenges, more and more Strata Corporations are adopting non-smoking bylaws that do NOT grandfather existing residents. This is supported by the Aradi decision in 2016 out of the BC Supreme Court, which upheld the Strata Corporation’s right to adopt bylaws which completely prohibited smoking without grandfathering existing smokers.

- Strata’s have a legal duty to accommodate an owner’s disability in relation to second-hand smoke exposure.

Stratas are subject to claims under Section 8 of the Human Rights Code, which states that a person must not be discriminated against regarding any accommodation, service or facility customarily available to the public. Regardless of what a Strata Corporation’s bylaws say about smoking, the Strata has a duty to accommodate any resident who has a legitimate medical condition that is adversely impacted by second-hand smoke. If a resident can prove that they have a medical condition or disability that is negatively impacted by exposure to second-hand smoke, they will establish a basic case of discrimination. Once discrimination is proven, then the onus shifts to the Strata to justify its actions, including showing that it has accommodated the complainant up to the point of undue hardship.

In Leary, the Strata was ordered to pay $7500 to an owner who suffered from asthmatic bronchitis for failure to take meaningful action to address her complaints of second-hand smoke.

Stratas also have a duty to address complaints of cannabis smoke, even in cases where a resident has approval for medicinal cannabis. In the case of

The Owners, Strata Plan LMS 2900 v. Mathew Hardy, 2016 BCCRT, the BC Civil Resolution Tribunal upheld a bylaw banning the smoking of medical cannabis. The tribunal found there was no reason the respondent couldn’t ingest his medicine rather than smoke it to protect neighbouring residents from the harms of exposure to second-hand smoke.

Steps for Addressing Second-Hand Smoke Complaints

Steps to address second-hand smoke:

For more information: check out case law highlights below.

Note: This section is for informational purposes only and is not intended to be and should not be construed to be legal advice.

pdf download - STRATA CORPORATIONS - How to Address Second-Hand Smoke Complaints - for printing

pdf download - STRATA CORPORATIONS - Guidelines for Responding to Accommodation Requests - for printing

(based on 2016 BC Human Rights Tribunal decision, Leary v. Strata Plan VR1001)

Steps for Addressing Second-Hand Smoke Complaints

If you are a Strata owner suffering from second-hand smoke infiltrating your home from a neighbouring residence, you are not alone. Over 50% of people living in multi-unit housing in BC have experienced second-hand smoke entering their homes from neighbouring units and balconies. (2018 survey)

There is no safe amount of second-hand smoke exposure. Second-hand smoke causes cancer and cardiovascular disease in non-smoking adults and numerous health problems in infants and children, including:

- acute respiratory infections

- ear problems

- more frequent and severe asthma attacks

- Wheezing and coughing

- sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)

If your Strata has a specific non-smoking bylaw, they have a duty to enforce the bylaw as they would any other bylaw infraction. However, regardless of whether or not your Strata Corporation has a specific non-smoking bylaw, your

Strata has a duty

to adequately investigate complaints of second-hand smoke (See Steps for Strata Corporations in the above section). All owners have a right to be free from behaviours that create a nuisance or hazard to their health, or that unreasonably interferes with the use and enjoyment of their home. If you are suffering from extensive and ongoing smoke infiltrating your home, your Strata must address the issue and take action to enforce the bylaws.

Note: If you have a pre-existing medical condition or disability, you may have a claim under the Human Rights Code. If this is the case, you should notify your Strata Council that you are seeking accommodation in relation to second-hand smoke. For more information, read the Strata Corporation resource: Guidelines for Responding to Accommodation Requests above in the Strata Corporation section.

Steps to address second-hand smoke:

pdf download - STRATA OWNERS - How to Address Second-Hand Smoke Complaints - for printing

Legal Information

Non-Smoking Bylaws are Legal in BC

We hear from many condo owners who are regularly exposed to their neighbours' second-hand smoke and want their strata to adopt a non-smoking bylaw. Many are unsure about the laws and whether non-smoking bylaws are discriminatory or simply unenforceable.

The good news is that non-smoking bylaws are legal, non-discriminatory AND enforceable. A non-smoking bylaw is no different than a bylaw that prohibits pets or barbeques.

This section describes provincial legislation and local government bylaws that govern smoking in strata complexes in BC.

- Provincial legislation

- Strata Property Act

- The Tobacco and Vapour Products Control Act

- Cannabis Control and Licensing Act and regulations

- The Human Rights Code

- Municipal governments:

- Many local governments have smoke-free bylaws to restrict smoking in public places, and some laws are stricter than provincial legislation.

- Enforcement of government smoke-free legislation

- Case law highlights and common questions on second-hand smoke in multi-unit housing

This section provides a brief description of the laws and regulations that govern smoking in Strata Corporations in BC.

pdf download - STRATA CORPORATIONS - BC Laws - for printing

Below are five cases from the BC Civil Resolution Tribunal and the Human Rights Tribunal where Strata Corporations have been held liable for failure to adequately address complaints of second-hand smoke exposure. Read the full list of cases we have highlighted in the downloadable PDF at the end of this section.

pdf download - STRATA CORPORATIONS - Case Law Highlights: Second-Hand Smoke Complaints in Strata Complexes - for printing

pdf download - STRATA CORPORATIONS - Guidelines for Responding to Accommodation Requests - for printing

Common Questions

pdf download - STRATA CORPORATIONS - Common Questions - for printing

Tools & Resources

This section provides a range of tools, downloads and links to assist with addressing second-hand smoke and developing, implementing and enforcing smoke-free policies in Strata Corporations.

Tools

pdf - Strata Guide on How to Address Second-Hand Smoke Complaints

pdf - Guidelines for Responding to Accommodation Requests

pdf - How to Create a Non-Smoking Bylaw for Existing Buildings

pdf - How to Create a Non-Smoking Bylaw for New Buildings

pdf - Top 5 Reasons for Adopting a Non-Smoking Bylaw

pdf - Strata Corporations - Common Questions

pdf - Case Law Highlights - Second-Hand Smoke Complaints in Strata Corporations

link

-

Strata Alert:

A Helpful Guide for Responding to Bylaw Infraction Complaints

Legal Resources

Provides an affordable way to resolve disputes without needing a lawyer or attending court.

Provides subsidized legal aid to British Columbians.

Community Legal Assistance Society (CLAS)

Provides legal assistance to low income British Columbians or those with physical or mental disabilities. CLAS also provides assistance through the UBC Law Students Legal Advice Program.

Call 604.685.3425

Law Students’ Legal Advice Program

UBC law students provide legal advice and assistance for people who are physically, mentally, socially, economically or otherwise disadvantaged or whose human rights need protection.

Provide free legal services for people who need help with human rights complaints.

Disability Alliance BC

Their

Disability Law Clinic is able to provide free legal advice and representation to people with disabilities who are dealing with human rights violations and discrimination.

A quasi-judicial body that deals with human rights complaints that are covered by the BC Human Rights Code. Resolution can be done through mediation or in a hearing.